The theory of reserve accounting is simple. Take the cost of the item (say, $100,000 for a roof) divide by its life expectancy (say, 20 years) and deposit that much per year into the reserve fund.

Repeat for every item on the list.

There are some tweaks and adjustments, including interest and inflation, but that’s the basic idea.

It works okay for new condominiums. In the early years, when few repairs are needed, it makes sense to put away money for painting and roof repair. But as buildings age, fully funded reserves, or even close to full funding, are rare.

Conventional Reserve Funding

Condominium reserve funding sounds good on paper, but there are practical reasons why so few older condominiums have sturdy reserves.

Here are the big ones, beginning with how saving for the future goes against the way human beings are hardwired.

1. Going Against Human Nature

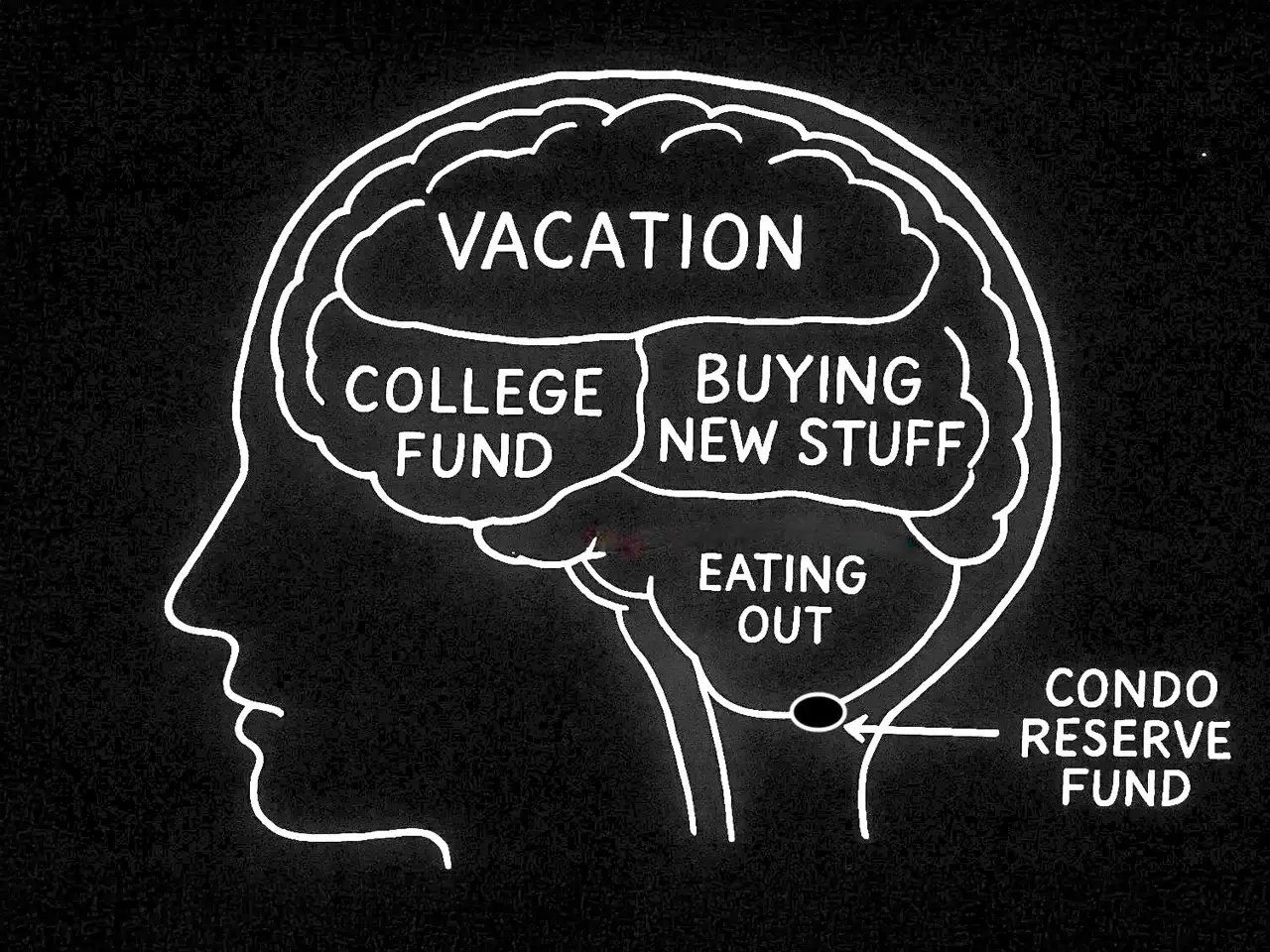

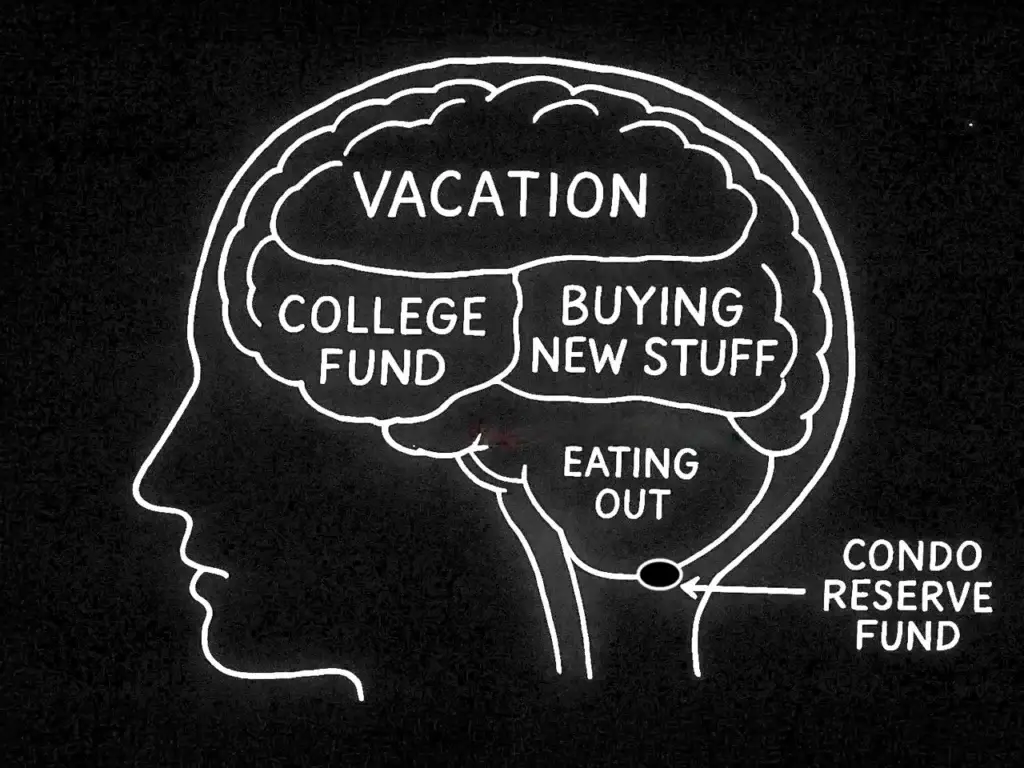

Psychology has a name for it: temporal discounting. It means that people prefer immediate rewards and discount the value of future benefits.

Temporal discounting predicts that most people would choose lower monthly assessments (often called “dues”) over a payment structure that puts away realistic sums for big repairs that will happen in the future.

This is true even for people who own their own homes. Does anyone put a new roof on their house, and then immediately start saving to replace it in 20 years? Nope. Let their “future self” worry about it.

In the case of condominiums, though, the “future self” who will benefit from having a tidy reserve fund in 10, 20 or 30 years is probably not even the person who is paying dues right now. Instead, it’s whoever owns the unit when the money needs to be spent.

2. Skewed Markets

One could still make a rational decision to save up for the future homeowner—if the market rewarded condos that put away proper reserves. But it doesn’t.

Instead, the incentives run in the other direction. Condos with low dues (even obviously unrealistic dues) are easier to sell. Condos with higher dues sit on the market longer or sell at a discount.

3. Limits on Investing Reserve Funds

By California statute, HOA reserve funds must be in federally insured accounts in a bank, savings association or credit union.

In the 1980s when condominiums were booming (and many concepts of proper reserve funding were first developed), HOAs could safely invest their funds at interest rates that were much higher than they are now. As of this writing, interest rates are about 4% on certificates of deposit.

Most owners don’t want their money sitting in the HOA’s bank account, earning little or no interest. They say they would rather invest their money themselves and pay special assessments when the time comes.

4. Taxes Take a Cut

It gets worse. What little interest HOAs receive on their reserve accounts is taxed at the federal level.

Most HOAs are nonprofit corporations that are eligible for special tax treatment under Section 528 of the Internal Revenue Code. Under Section 528, HOAs pay no tax on what they collect from their unit owners as dues or special assessments, called “exempt function income.”

Interest on the reserve account, however, is taxable on the Federal level. At 30%.

What Should a Rational HOA Do?

It’s a steep, uphill climb. Getting today’s owners to save for the future is particularly difficult if the past owners didn’t reserve for them. Changing a building’s culture from pay-as-you-go to fully funding reserves means that the current owners are hit up twice: once for the current repairs that their predecessors didn’t save for, and again to benefit future owners.

For money that is contributed to reserves, the math is inescapable. If reserves in a CD earn interest at 4%, the after-tax interest is 2.8%.

So is it rational to put money away in a reserve account on a 30-year schedule where it will appreciate far less than the rate of inflation?

Or more rational to find other ways to fund needed repairs?

Are HOAs Required to Fully Fund Reserves?

Civil Code §5600 requires boards to levy regular and special assessments sufficient to perform its obligations under its governing documents and the Davis-Stirling Act.

Under Civil Code § 5550, the board must do a reserve study every three years. Reserve studies include lengthy calculations for funding the reserves going out 30 years, and the percentage funding that would result. (As noted in a companion CondoWonk article, these reserves suffer both by missing certain expenses and including a daunting list of dubious items, which means that the whole complicated calculation starts with an extremely shaky premise of what will be needed in the future.)

Does the statute say that the only way to use the reserve study is to fully fund reserves for every item in the study?

A reminder: I’m not licensed as an attorney in California and this is not legal advice.

But here’s a summary of the law written by a law firm that specializes in HOA issues.

That discussion states, “Even though there is no mandate by the legislature to fund reserves, the prudent course is to fund reserves according to the association’s reserve funding plan.”

Otherwise, the article continues, the HOA will need to rely on special assessments or bank loans to fund repairs. The article also states that underfunded reserves can decrease property values and cause problems with lenders and insurers.

Another Approach

That’s the conventional wisdom.

For older buildings facing large repairs and little-to-no reserves, we may need to admit that the goal of funding reserves 30 years into the future is unrealistic.

More modest reserves to cover smaller, more immediate projects plus special assessments or loans or both as needed may be more realistic than trying to save decades ahead for an unknowable future.

Final Thoughts

I’m a fan of realism. For buildings that are 30, 40 or 50 years old, the HOA needs to focus on maintaining the condominium property for its present occupants and make the kinds of repairs necessary to preserve the building. Failure to do that now may result in far more costly repairs or shorten the building’s useful life.

If I had to pick between fully funded reserves and current maintenance, I’d focus on fixing leaks. Every single time.

Your HOA should check with your attorney before abandoning its 30-year funding plan.

As reported in a companion article, there are problems with reserve studies. Our reserve study bogged down with questionable small items while missing some huge issues.

In upcoming articles in this series, CondoWonk will look at the lessons learned from the collapse of the Champlain Towers, and some alternative ways to think about caring for older buildings.

See Also: Companion Article, Anatomy of a Reserve Study