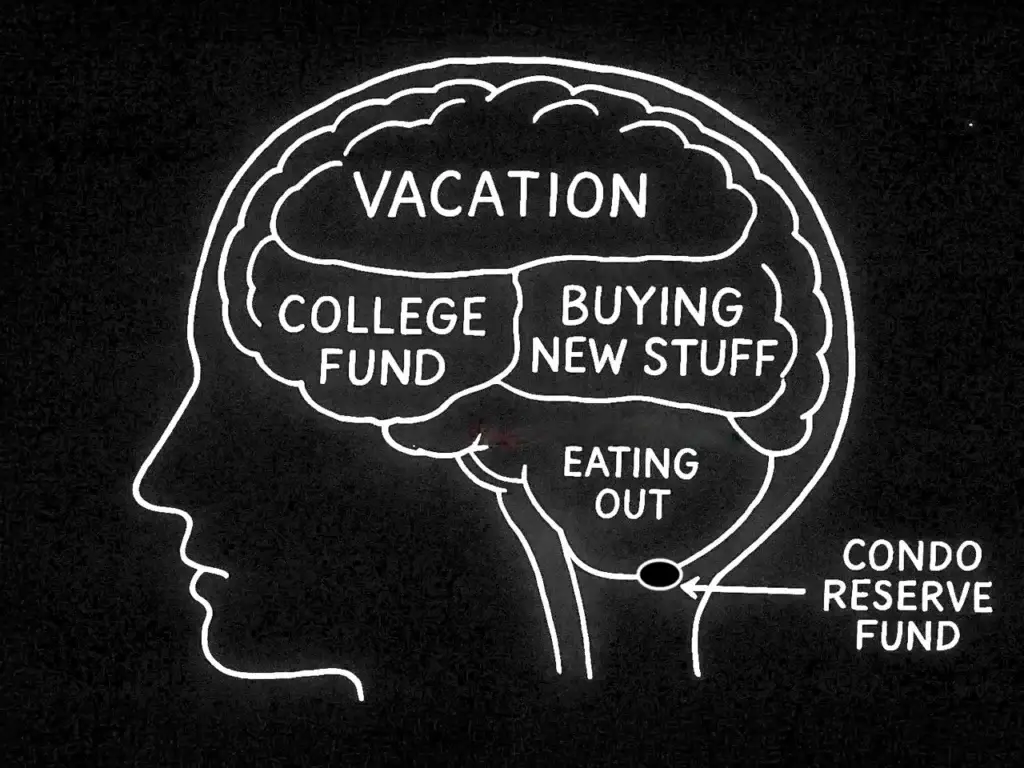

The former president of our HOA used to hold the latest reserve study aloft at a meeting and make a big show of ignoring it. The dues increase needed to fully fund reserves would be unthinkably large. Why even try?

As it turned out, the number in the reserve study wasn’t big enough.

The study, required to be performed every three years under California law, seemed thorough. Picky, even. It made digs at our lobby furniture, gym equipment and functional but dated-looking pool bathrooms and dutifully assigned a dollar value and estimated useful life to each. Yet despite this apparent thoroughness, it contained critical reserve study mistakes that would cost us dearly.

But it had major omissions, including a critical project that we had to fund with the largest special assessment in our building’s history.

The Largest Reserve Study Mistake

Our reserve study considered our wood shingle siding to be a lifetime element, needing only paint and periodic repairs of localized issues.

The building was built in 1986. In the past, every 8-10 years the HOA would paint the building and replace any areas of rotted shingles. The most recent patch and paint job, in 2018, cost $100,000.

Those days are over. Back-to-back rainy winters—a local weather record—revealed large areas of our building with rotted wood resulting in major leaks.

An Expensive Project

Instead of patching, we needed to strip off all the old wooden shingles, remove the deteriorated waterproofing layer and rotted plywood, and rebuild the plywood, waterproofing and siding.

Wooden shingles are no longer permitted as a construction material in our area. Instead, we completed the siding with Hardie-brand shingles, a cement fiber material that looks remarkably like our old wooden shingles but rarely needs painting and resists rot, termites and, significantly, fire.

Hardie was just starting to be produced around the time our building was constructed. It is superior to wood—with luck, the reconstruction will last 40 years—but it is far more expensive.

The cost for the entire building was estimated at $1 million, ten times the cost of the previous patch-and-paint jobs. We opted to do the two sides of the building most damaged by sun exposure and are now doing the rest in stages.

Even doing half the building was a massive special assessment, dwarfing any our building had ever experienced.

Waterproofing with an Expiration Date

In addition to the wood siding, our reserve study missed another obvious long-term issue.

In the center of our building is a landscaped atrium. It’s essentially a giant planter box sitting on top our garage.

Lately we’ve noticed some small leaks in the garage. We’ve been told that the waterproofing material applied to the atrium walls is well past its life expectancy and has worn out.

In the next few years, we will likely need to excavate the atrium, repair the waterproofing and then replant. If we ignore it—we won’t—it could eventually weaken the concrete structure.

What’s Supposed to be in a Reserve Study

Under Civil Code § 5550, a reserve study is supposed to list all “major components” that the association is responsible for repairing, restoring, replacing or maintaining.

There are two problems with that statute that often lead to reserve study mistakes. Components. And major.

The statute doesn’t define either.

What Reserves May be Used For

On the flip side, Civil Code § 5510 states that the board may expend reserve funds only for major components that the association is responsible for repairing, restoring, replacing or maintaining. This is to prevent the HOA from frittering away its reserve funds for operating expenses.

So the reserve study must cover all major components, while HOAs can withdraw from their reserve funds only for major components.

This implies that there is a clearcut definition for major components. Again, I couldn’t find one in the statute. Here’s what I found instead.

What’s a Component?

Everyone agrees that to be included in the reserve study, it needs to be a component for which the HOA is responsible, and which has a remaining useful life of less than 30 years. But those are attributes, not a definition.

Does a component need to be attached to the building? Does it need to be critical to the operation of the building or its structural integrity? Or can a study decide that something needs replacement simply because it looks dated?

The only article I could find that wrestled a bit with the definition of a component was a Community Associations Institute (CAI) article dated 2023 that is not specific to California. It provided this intriguing insight:

Components are not restricted to physical items. Components may be projects that do not particularly involve the repair or replacement of a physical asset. In many cases, “components” may not be tangible objects or visually observable yet but should still be considered for inclusion in the study based on the expertise of the reserve study provider, a review of any available design drawings, or other subject matter experts.

That’s clear, right? Uh, no. This ambiguity is one of the root causes of reserve study mistakes across California HOAs.

And What’s Major?

And as to what is considered “major” the same CAI article stated that a project is major if its cost can be reasonably estimated, including all direct and related costs, and “is material to the association.”

A publication from the State of California Department of Real Estate, dated 2010, says,

One possible guideline is to include items that cost 1% or more of the total annual association budget. Another possible guideline is to include items that cost over $500 or over $1000 to replace, including groups of related items (e.g., all gates in the development) that cost over $1000 to replace.

The DRE further suggests that the board should discuss and adopt guidelines for the dollar amount or percentage to use for the reserve study.

Taking Control of Your Reserve Study

I concur. Reserve studies have become bloated over time. In the interest of looking thorough, those in the business of performing reserve studies cast a wide net of what to include.

Before your reserve study is written, discuss with your board, and your vendor, what items are significant enough to be included, setting a dollar value for inclusion and deciding whether to include items that are aesthetic rather than necessary for the building’s integrity and operation. This proactive approach can help you avoid costly reserve study mistakeslike the ones that blindsided our HOA.

Weaknesses in the Process that Cause Reserve Study Mistakes

So how did we end up with a 130-page reserve study that took offense at our dated-looking pool restrooms and lobby furniture, but missed truly major issues? Understanding how these reserve study mistakes happened is crucial for preventing them at your HOA.

The life expectancy of wood siding is a known blind spot and may have originated in the developer’s budget disclosures when our building was created and marketed in 1986. As the organization ECHO describes, state budget guidelines at the time omitted reserves for replacement of wood siding, apparently presuming that painting was sufficient.

As to the atrium waterproofing issue—a giant planter box sitting on top of the garage— it should have been obvious to anyone trained to evaluate HOA repair obligations.

Both of these concerns may also have missed inclusion as being outside the 30-year window when the building was new. Later studies apparently just copied and pasted.

That doesn’t excuse it. But it may explain how these reserve study mistakes become so widespread throughout the industry.

Final Thoughts

Whatever the source of the reserve study mistakes, our studies were deeply flawed. They missed major, expensive repairs that we didn’t see coming.

But it also muddied the waters with a lot of irrelevant junk. That list of nonessential items takes the focus away from what is important: the structural integrity of the building and the operation of its various systems.

Those directory boards mentioned in 2018 have since been discarded entirely. Our new entry system includes an easily updated printed directory instead.

Our latest reserve study says our new tamper-proof mailboxes will need to be replaced in 30 years. One wonders if postal delivery service will last that long.

I’m not opposed to the idea of reserve studies. But it’s time to rethink how they are performed in California.

What’s in your reserve study?

Companion Article: A Rational Approach to Reserve Funding